Natural Sovereignty, Paolo Cirio’s solo show at the Saint James’ Charterhouse in Capri.

In Paolo Cirio’s solo show, Natural Sovereignty, exhibited at the museum MiBACT Certosa of Capri, the artist presents a utopian vision of climate justice, using the conceptual framework of a “climate crime tribunal” that unfolds in the halls and cloisters of the Saint James Charterhouse.

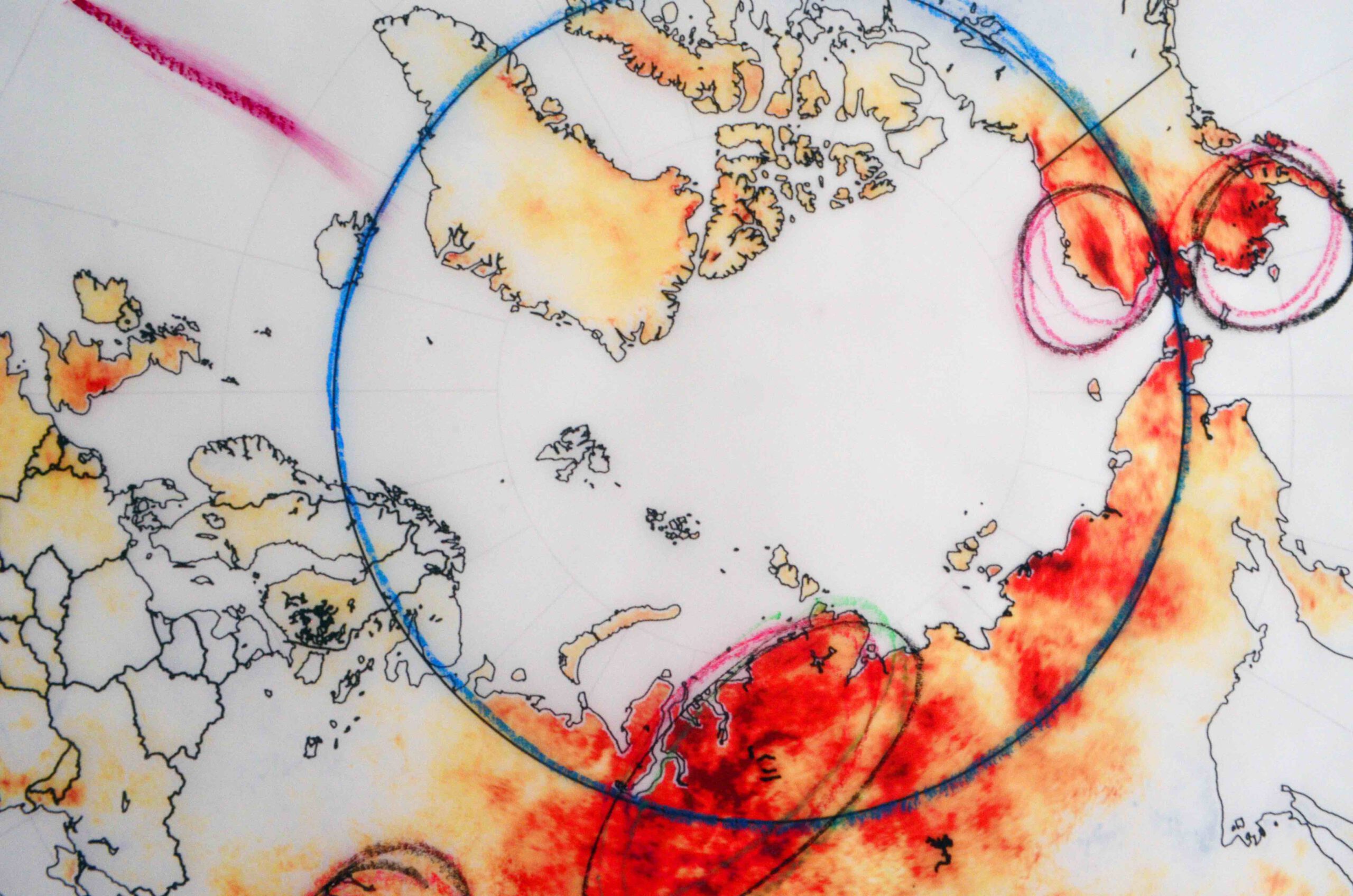

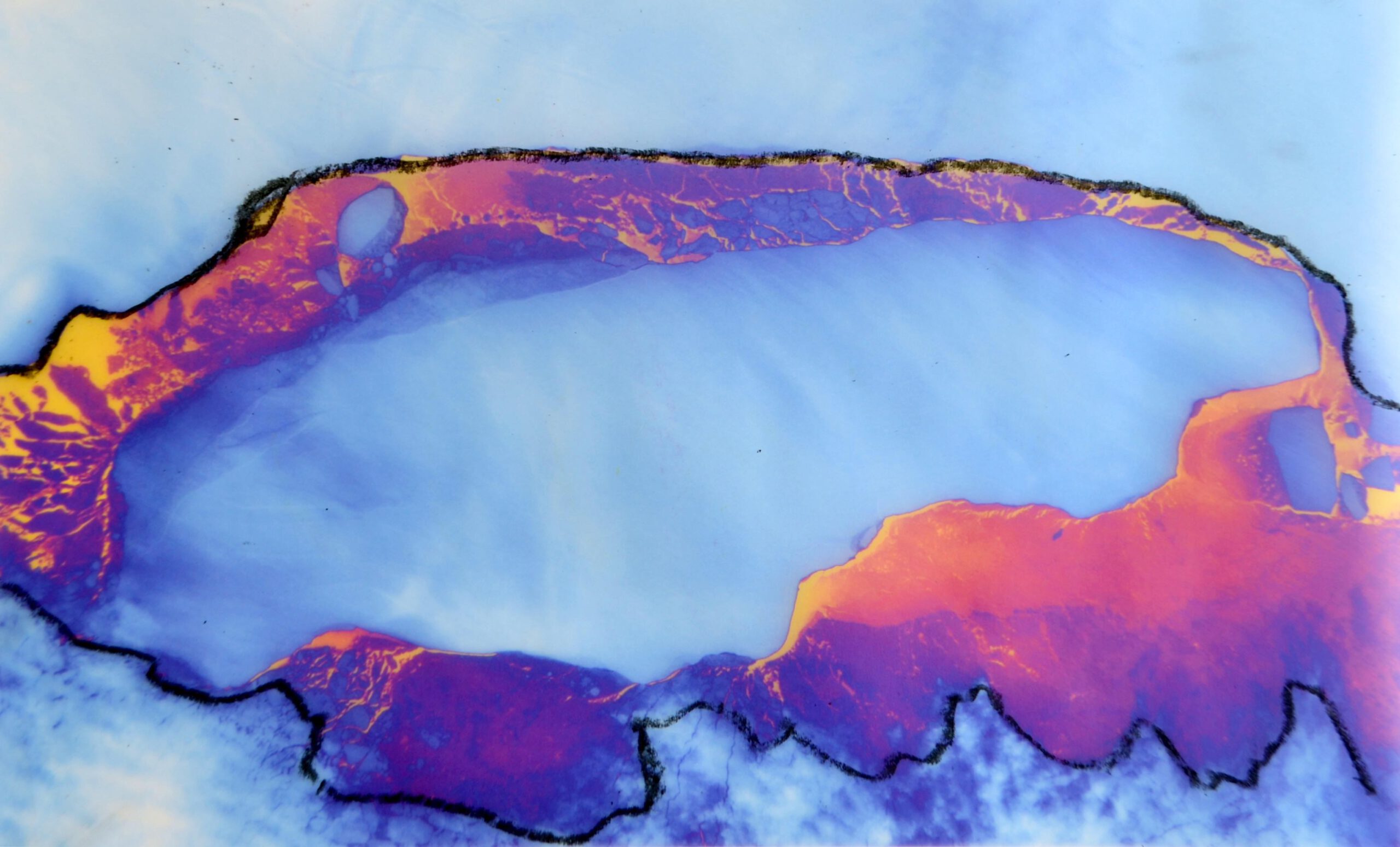

Cirio presents the international tribunal of climate crimes with a vast body of material drawn from his research on the climate crises. Using prints on canvas, fabric and paper on which he intervenes, Cirio’s informational visuals feature scientific and economic data, legal documents and biological studies. The colors, notations and compositions highlight specific evidence that illustrate the legal accountability fossil fuel companies have, creating greater public engagement with this complex theme.

Cirio aims to shift the cultural perspective on the responsibility for the current climate and ecological crisis, from individual citizens to the real culprits that remain unpunished. With this provocation, Cirio accuses the major oil, gas and coal companies in court with data and documents on climate change that directly correspond to their greenhouse gas emissions. The tribunal enables thousands of natural species–including humans– and damaged ecosystems to seek financial compensation from those who have caused the climate crisis on a massive scale. Court documents and graphics are presented as evidence, climate crisis experts intervene as witnesses, and visitors to the exhibition participate as a jury, with the potential to evaluate the evidence or identify as an injured party.

In this exhibition, the concept of sovereignty is extended to the natural world and envisions a future in which human beings, natural species and ecosystems acquire supranational rights codified by international public laws. The future climate policy will not only have to include a transition to more sustainable economies; it will ultimately require rebuilding economic, social and natural systems from climate disasters, and holding those who have caused damage of unprecedented proportions accountable for their actions.

Cirio’s new works utilize art’s versatility to illustrate the scientific, legal, and economic issues that humanity must face with climate change. Cirio’s networks of data propose connections between the information systems of science, law and economics, which are integral to natural ecosystems. As humans have altered Earth’s ecosystems and severely exploited it’s natural resources in the Anthropocene, we should conceive of the economic, social and information systems as the nerves of this new geological era.

The sovereignty of the future will inevitably be given back to nature. Climate change will overrun our inflexible human systems with its natural laws, forcing humankind to adapt to new realities. The concept of justice will evolve into a larger interconnected system, in which natural species, ecosystems and humans may constitute themselves as climate victims, while corporate and political entities will be identified as criminals. The design of such a system includes data, networks and algorithms that process climate, biological and ecological information to find economic, social and legal balances on a planetary scale. In the future of the Anthropocentric age, humans and the environment must be positively interconnected in order to achieve peaceful coexistence.

In the halls of the Certosa of Capri, Cirio exhibits hundreds of images depicting ecosystems, flora and fauna that are at risk of extinction, and places them in dialogue with the economic and political factors that have critically endangered them. In the largest cloister, twenty-four flags representing the fossil fuel companies that emitted over 50% of the World’s greenhouse gasses are blacked with oil. Graphs, data, maps and images of climatic and economic anomalies are presented as comparative juxtapositions and points of analyses. Adjacent to these evidential documents, is a sound installation in the Certosa garden exhibiting interviews that Cirio conducted in conversation with international experts in the field of climate justice. In the final room, a participatory artwork invites the public to express their opinions as members of the tribunal’s jury. Together, these works compose an atlas of ecological and human coexistence – Cirio’s initial step towards the creation of a museum of climate justice for the 21st century.

Capri provides a fertile context and ideal space for the exhibition. Located in the center of the Mediterranean, with its peculiar biodiversity, the island becomes symbolic of the fragility and centrality of nature within human civilizations. Moreover, the political and transnational history of the island, from being the headquarters of Roman Emperors to Lenin and his Social Democratic Schools for Underground Party Workers, echoes Capri’s history of modern art and natural sciences, hosting visionaries such as Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, Joseph Beuys, and Edward.

About the Saint James’ Charterhouse in Capri, Italy.

The Saint James’ Charterhouse (Certosa di San Giacomo) is a monastery on the island of Capri built in 1371 that now stands as a cultural museum run by the Italian Ministry for Cultural and Environmental Heritage (MIBAC).

Capri may be well-known as a world-renowned hotspot and tourist attraction; however, it is also an archeological and historical site for artists and humanists concerned with environmentalism. In the mid-late 20th century, Capri became a designation for an international roster of artists, writers and environmentalists, including the likes of Thoman Mann, Norman Douglas, Edwin Cerio, Pablo Neruda, and Friedrich Alfred Krupp, amongst others. One such transplant, Swedish writer Axel Munthe, resided in Villa San Michele, which now functions as an international cultural center and the Swedish Honorary Consulate. Vladimir Lenin created the Social Democratic Schools for Underground Party Workers in Capri from 1909-11, where he held meetings with the socialists Maksim Gor’kij and Alexander Bogdanov. Joseph Beuys lived in Capri in 1974 while healing from an illness, when he composed the beloved artwork, Capri Batterie, which was dedicated to the island. Capri environmentalists include Edward Cerio and Friedrich Alfred Krupp, the German steel magnate with a passion for marine biology and the arts. During the early 1900’s, Krupp personally collaborated with the Naples Zoological Station.

A lesser-known Caprese, Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, was a German painter, naturalist and social reformer, who pioneered the peace movements and established his community in Capri in 1899. Diefenbach explored life in harmony with nature, the rejection of monogamy, and a vegetarian diet, and has artworks exhibited in the permanent collection of the Certosa of Capri.